By Caroline Harbison, Eleanor Matthewman, Eimear North, Miriam Olsen, Amy Rakei

We are living longer, that is a fact! In the last 20 years, the average life expectancy in the UK has increased from 78- to 81-years-old, mainly due to advancements in medicine, nutrition and lifestyle. But living longer comes at a cost. This improved life expectancy has caused additional strain on our physical and mental health, and consequently an increase in neurodegenerative conditions such as dementia. Dementia, a syndrome primarily associated with the aged population, is characterised by a decline in brain function. Dementia affects millions of sufferers and families worldwide with cases rising year on year. There are currently around 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK alone.

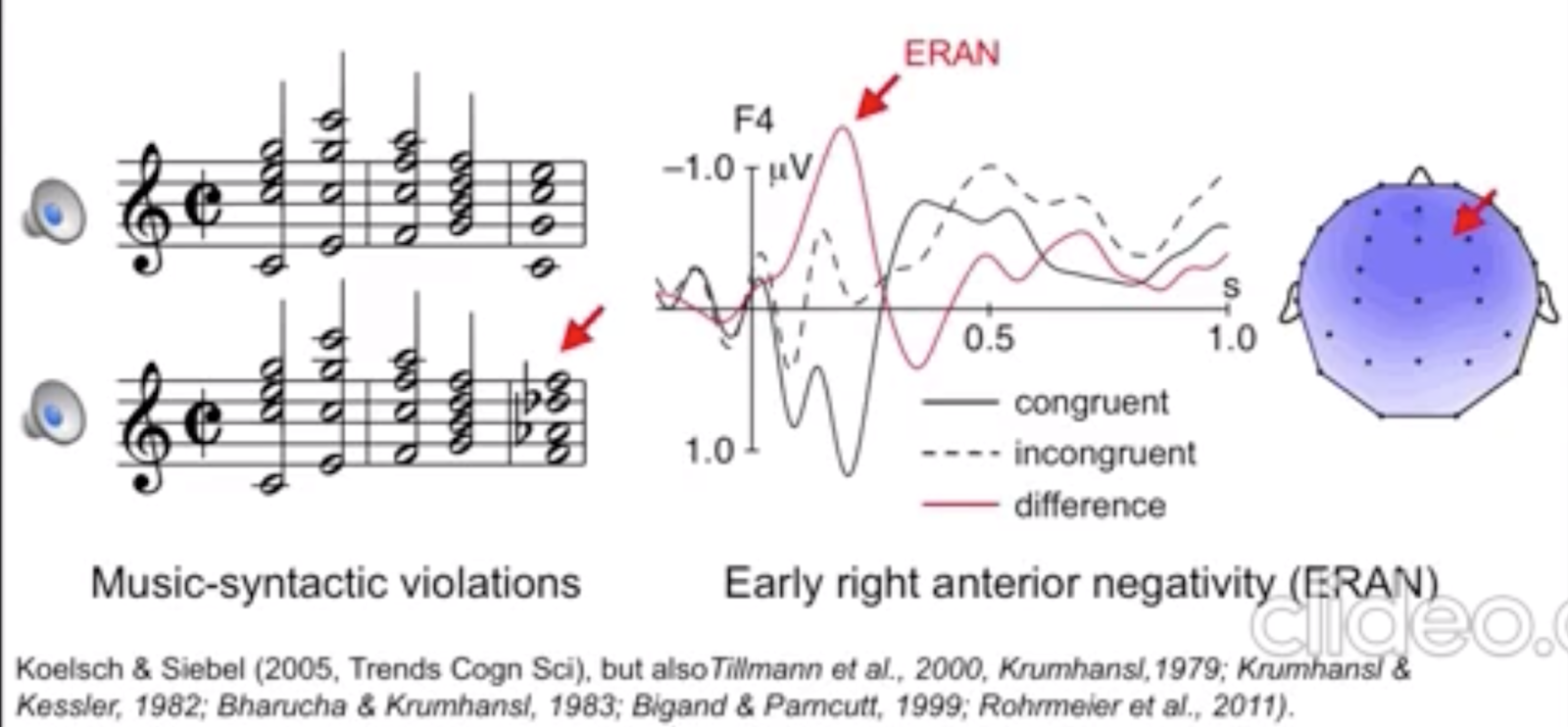

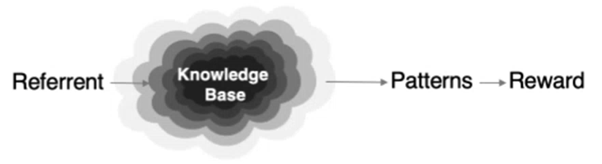

Researching the brain is highly complex so let’s dig into the science briefly. As we get older, proteins, which are an essential part of every living organism, can become pathogenic (disease-causing). A healthy functioning brain relies on neurotransmitters, chemical messengers associated with the communication of brain cells, and proteins for brain stability and health. This intelligent organ uses neural proteins for predictive coding, a basic function to predict sensory input such as hearing, to accelerate a specific response and reduce reaction time. However, sometimes pathogenic neural proteins can lead to broken neural pathways causing common dementia symptoms. The big question of what pathogenic proteins are associated with different dementia types is still poorly understood, making early diagnosis difficult.

There are numerous types of dementia, the most common being Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), which involves the loss of episodic memory: memory of events, situations and experiences. Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is a less common form of dementia, characterised by problems with behaviour and language. Subtypes of FTD include bvFTD, nfvPPA and svPPA, involving behavioural change, speech production difficulties and loss of semantic knowledge (aphasia), respectively (Alzheimer’s Society, n.d.). Unfortunately, there are no treatments that can cure these diseases, or stop the degeneration. However, there are medications available that can lessen symptoms and slow progression. Early diagnosis allows patients to receive the right treatment and support. Currently, there is no “go-to” method of diagnosing specific types of dementia, especially early in disease progression, but scientists are working tirelessly on developing innovative tools to make this possible. One such tool showing incredible promise for early diagnosis is music.

While some cognitive functions may be lost in patients with dementia, the widespread neural complexity of music processing means it is less susceptible to progressive damage. Music can be used both recreationally and in clinical settings to soothe dementia patients. Music therapy can be used to treat and ease symptoms while also being very enjoyable for the patients. People with dementia participate in music-making sessions, by either singing, listening to music or playing an instrument. Researchers Wall and Duffy (2010) analysed the benefits of music therapy and found it can reduce anxiety and aggression, restore cognitive and motor functions and generally improve quality of life.

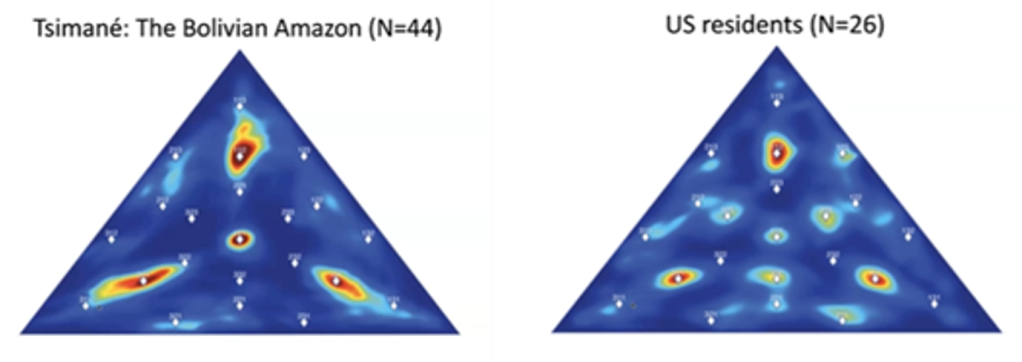

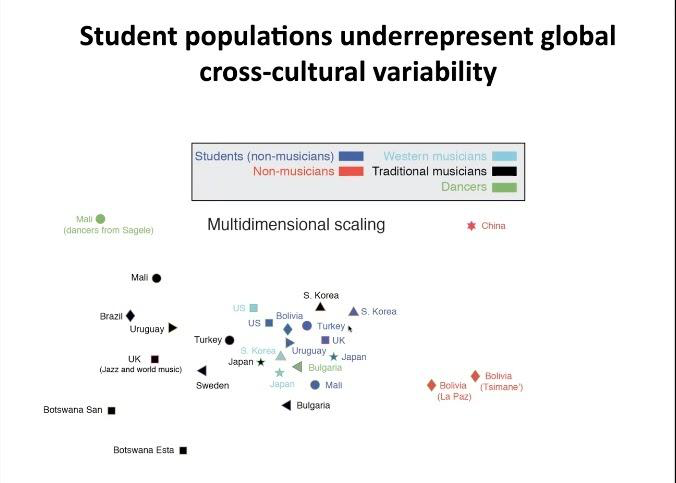

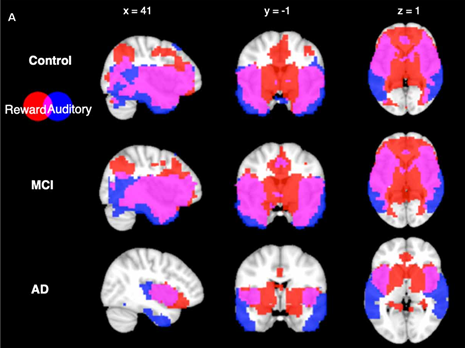

Music is useful in dementia research for several reasons (Benhamou and Warren, 2020). Firstly, music is highly codifiable and it involves the whole processing hierarchy of the brain (Peretz & Coltheart, 2003), allowing more neural connections to be utilised. Secondly, no musical training is necessary. Finally, music has the power to cut through cultural and language barriers and can evoke strong physiological responses which are easy for researchers to measure (Carpentier & Potter, 2007; Landreth & Landreth, 1974). For these reasons, Elia Benhamou, a clinical neuroscientist at the Dementia Research Centre at University College London, uses music as a tool to probe behavioural and physiological changes due to the deposition of pathogenic proteins in different forms of dementia and make early diagnosis easier.

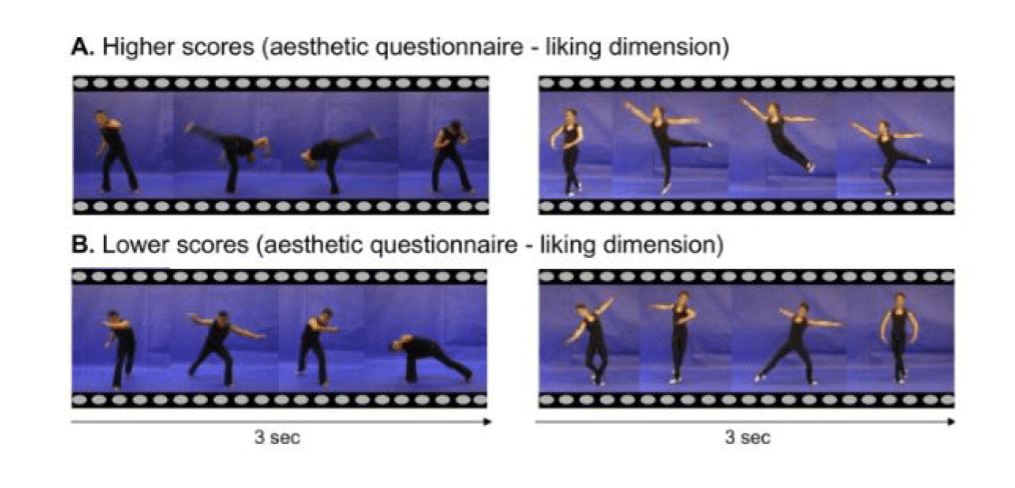

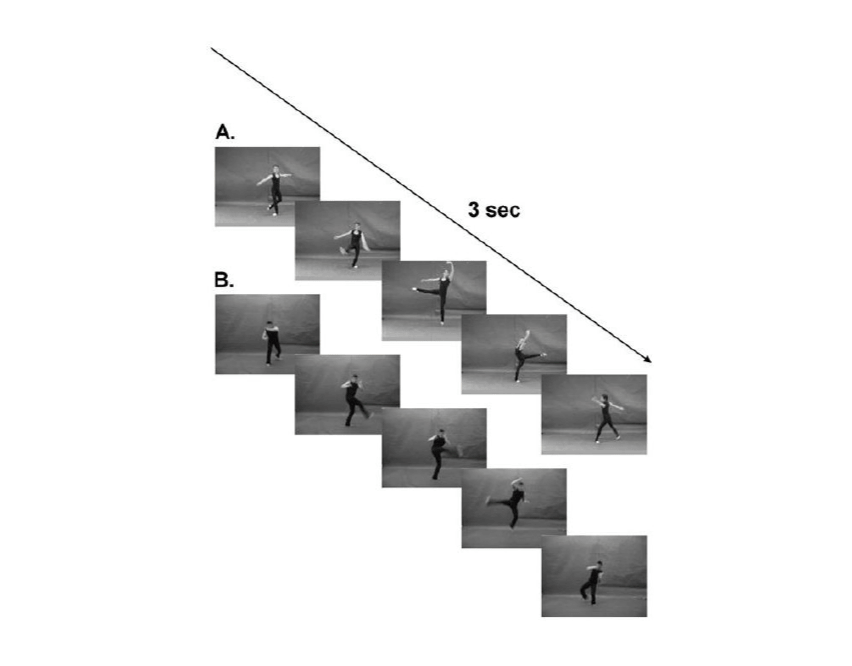

When we listen to a piece of music, our brain generates expectations to which incoming information can be compared on multiple levels. Benhamou’s research (Benhamou et al., 2021) examines how these predictive cognitive processes may be impaired in AD and FTD patients. Although their behavioural responses to music have previously been measured (Johnson & Chow, 2015), Benhamou also measured pupil responses as an additional physiological parameter, thus providing additional information about the characteristics of each syndrome. In an experiment studying musical expectations based on prior knowledge, participants were exposed to a range of familiar melodies where a single note was replaced by white noise, an out-of-key note or a different in-key note. Whereas AD patients showed similar responses to the control group, FTD patients showed impaired musical surprise processing on both a syntactic and semantic level. nfvPPA patients were particularly interesting as, in contrast to other FTD patients, they displayed slightly enhanced pupil responses for all melodic deviants, indicating this syndrome exhibited different behavioural and physiological profiles of musical surprise processing. A second experiment focusing on the tracking of deviations in unfamiliar melodic sequences revealed nfvPPA patients were still able to successfully track and identify melodic deviations through processes of statistical learning, whereas other FTD patients showed different levels of impairment both in the behavioural and physiological responses. These findings can help us create pathological profiles relating to musical surprise processing for these different dementia syndromes, which could eventually become a useful tool for early diagnosis.

Benhamou’s research has contributed to a deeper understanding of the behavioural and physiological differences in these types of dementia. Her research brings us one step closer to earlier diagnoses and a more accurate stratification of dementia. She has also shownusing music instead of language (which becomes impossible in patients with aphasia) provides an enjoyable, engaging and relaxing experience for dementia patients. Benhamou and colleagues are breaking new ground and hoping to develop an intervention for patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and aphasia via a new app. This app will incorporate music tests and will be personalised to each specific syndrome and stage of the disease, allowing for the close tracking of behavioural changes. Music is a significant outlet for many people, especially when the world around them is becoming ever more confusing. When language is no longer accessible and friendly faces become unfamiliar, music can provide solace, which is precisely why research into dementia and music, such as Benhamou’s, remains as relevant and important as ever.

References

Alzheimer’s Society—United Against Dementia. (n.d.). Retrieved 10 April 2021, from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk

Benhamou E., Warren J. D. (2020). Disorders of music processing in dementia. In L. L. Cuddy, S. Belleville, A. Moussard (Eds.), Music and the Aging Brain (pp. 107-149). Academic Press.

Benhamou E., Zhao S., Sivasathiaseelan H., Johnson J. C. S., et al. (in press). Decoding expectation and surprise in dementia: the paradigm of music. Brain communications.

Benhamou, E. (2021). Predictive cognition in dementia: The case of music [PhD Dissertation]. University College London.

Carpentier, F. R. D., & Potter, R. F. (2007). Effects of music on physiological arousal: Explorations into tempo and genre. Media Psychology, 10(3), 339-363. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701533045

Johnson, J. K., & Chow, M. L. (2015). Hearing and music in dementia. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 129, 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00037-8

Landreth, J., & Landreth, H. (1974). Effects of music on physiological response. Journal of Research in Music Education, 22(1), 4-12. https://doi.org/10.2307/3344613

Peretz, I., & Coltheart, M. (2003). Modularity of music processing. Nature Neuroscience, 6(7), 688-691. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1083

Sacks, O. (2007). Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain. Knopf.

Wall, M. and Duffy, A. (2010). The effects of music therapy for older people with dementia. British Journal of Nursing, 19(2), 108-113. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2010.19.2.46295